Note: if referencing this webpage, please credit Norma Owens, citing the webpage title 'The Lost Letter' and including the webpage url and the date downloaded.

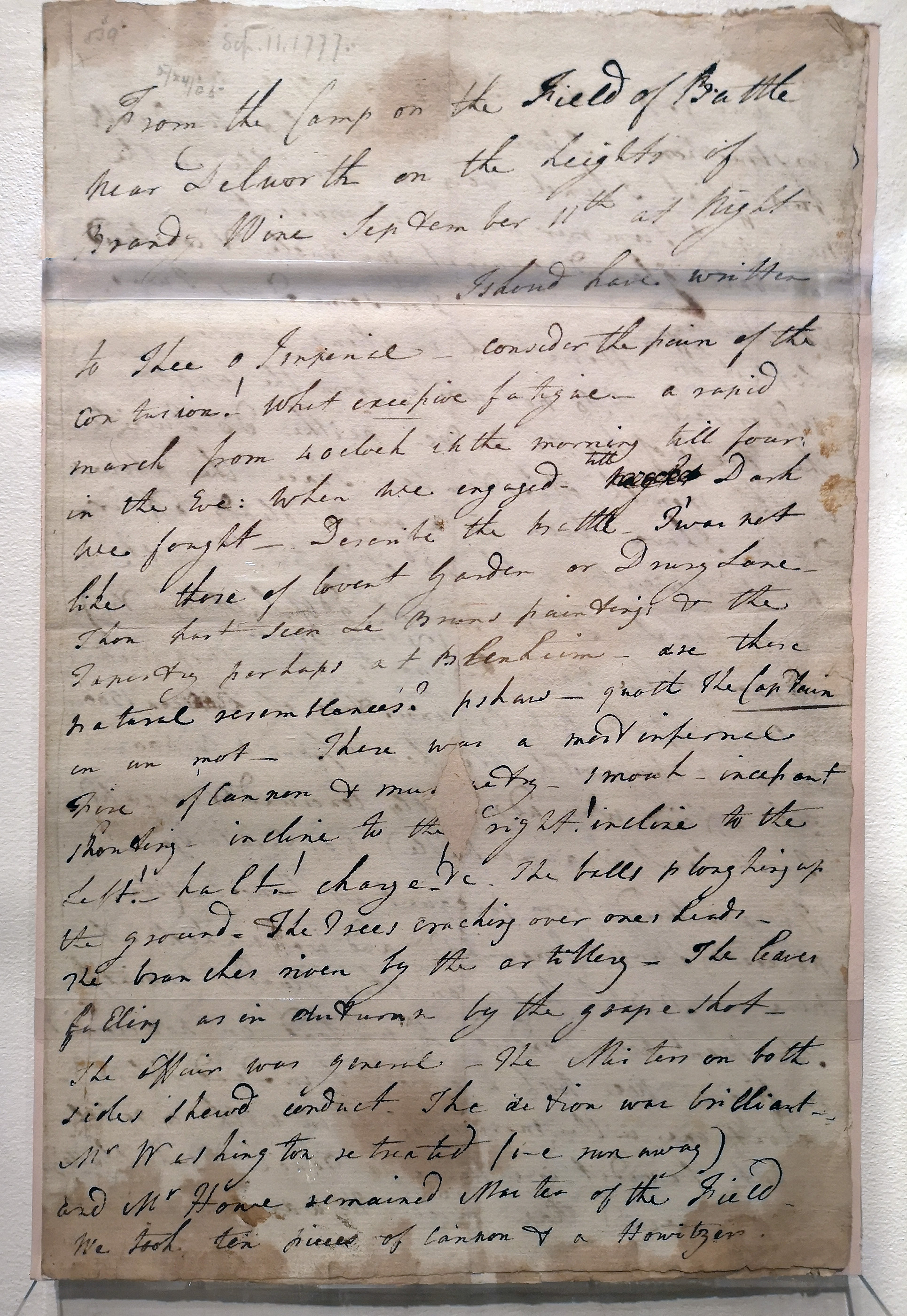

In 1777, during the American Revolution, General William Howe of the British army sailed his troops south from New York in a successful attempt to capture the American capital of Philadelphia. At the Battle of Germantown on 4th October, a letter written by a British officer was lost on the battlefield and recovered by American troops. It was passed to Brigadier General Anthony Wayne of the Continental Army and today is held in the collection of Wayne Papers held by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. The letter (reproduced in full below) was unsigned, and the writer therefore was a mystery for many years. However, research by Stephen Gilbert led him to identify the author of the 1777 mystery letter as Richard Mansergh St. George of Headford Castle, whose mother, Mary, had introduced lacemaking to Headford.

The letter now forms part of a remarkable exhibition called 'Cost of Revolution: The Life and Death of an Irish Soldier' curated by Matthew Skic of the Museum of the American Revolution. The exhibition focuses on the life of St. George and brings together for the first time twenty-two works of art created or commissioned by him, along with numerous other rare artefacts.

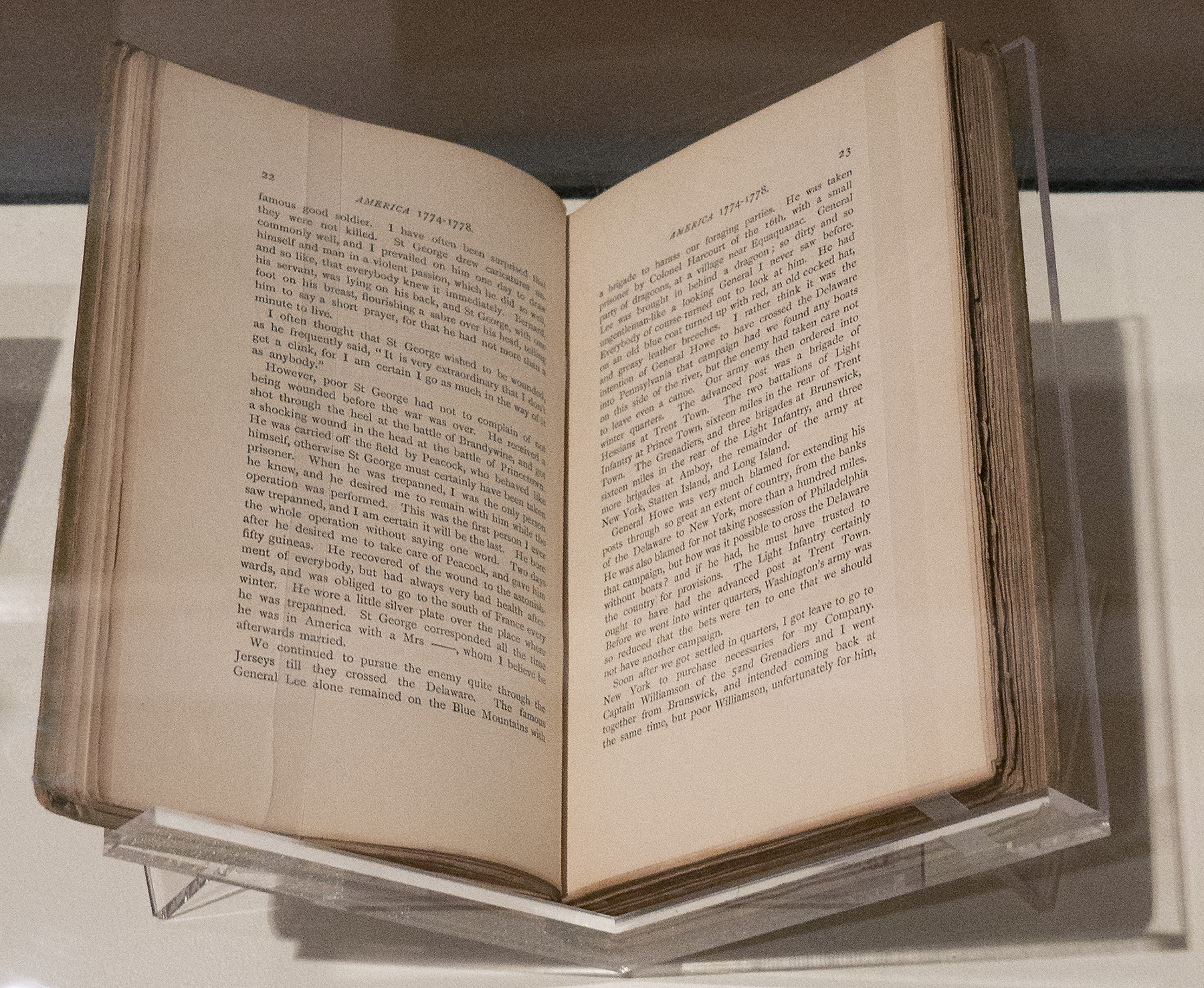

Letter written by Richard St. George in Pennsylvania on 11th September and 2nd October, 1777. From the collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and photographed at the 'Cost of Revolution: The Life & Death of an Irish Soldier' exhibition at the Museum of the American Revolution.

Richard Mansergh St. George at War

In April 1775, when the American Revolution started, St. George bought a cornet's commission (the lowest ranking officer) in the 8th Regiment of Dragoons - the same regiment in which his grandfather, Richard St. George of Athlone, had been a colonel. A year later, he purchased an ensign's commission in the 4th Regiment of Foot, which was already serving in America. Therefore in 1776, St. George sailed for New York to fight for the British Empire. Before he departed, St. George commissioned Thomas Gainsborough to paint his portrait.

Richard St George Mansergh-St George (1776) by Thomas Gainsborough. From the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Australia, and photographed at the 'Cost of Revolution: The Life & Death of an Irish Soldier' exhibition at the Museum of the American Revolution.

In the Gainsborough Portrait, St. George wears the uniform of an officer of the 4th Regiment of Foot. The silver gorget worn around his neck is descended from the throat guards worn by medieval knights as part of their suits of armour, and denotes his rank as an officer. Similarly, the red silk sash around his waist was worn only by officers. He is armed with a fusil and bayonet, and his silver-hilted short sword features a lion's head, a symbol of power commonly found on late 18th-century British swords that also indicates his rank. His buttons and silver belt plate are engraved with the Roman numeral 'IV' to signify the 4th Regiment. Although the loyal dog depicted in the portrait wears a collar of leather with a brass nameplate, its name is unknown. It is possible that St. George brought his spaniel with him to America, as some British officers did indeed keep dogs while on military campaign. Cost of Revolution: The Life and Death of an Irish Soldier (2019-2020) [Exhibition]. Museum of the American Revolution, 28 September 2019 - 17 March 2020. The ship in the background suggest that St. George is about to depart for foreign shores.

Later in 1776, St. George purchased a new commission, becoming a lieutenant in the 52nd Regiment's Light Infantry, which formed part of the army's 2nd Battalion of Light Infantry.Skic, Matthew, Cost of Revolution: The Life and Death of an Irish Soldier (2019), pp 17-18. He served in five battles in the area around Long Island, New York,Cost of Revolution: The Life and Death of an Irish Soldier (2019-2020) [Exhibition]. Museum of the American Revolution, 28 September 2019 - 17 March 2020. before sailing south under General Howe to fight in the Philadelphia Campaign.

Solving the Mystery: Who Wrote the Letter?

Stephen Gilbert used the clues in the lost letter to connect it to Richard Mansergh St. George. To start with, the letter writer says that he fought in the "the 2d of Light Infantry".Letter from Richard St. George to 'Imperial', 11th September and 2nd October 1777. Wayne Papers, Vol. 4. Historical Society of Pennsylvania. It is written in two parts, separated by several days, and includes details about the Battle of Brandywine and the Battle of Paoli. The letter was written by someone who was clearly very well-educated, which points to his being a wealthy officer.

Of course, St. George was not the only one writing accounts of his time with the British Army in Philadelphia: Sir Martin Hunter (1757–1846), a captain in the 52nd Light Infantry at the time and a close personal friend of St. George, wrote a journal that was published posthumously in 1894. Cross-referencing details in the letter with Hunter's account helps to ascertain more information about the writer's identity. Hunter mentions St. George several times. He writes: St George and I were great friends. He was a fine, high-spirited, gentleman-like young man, but uncommonly passionate. [...] He received a shot through the heel at the battle of Brandywine".Hunter, Martin [edited by Dickson Hunter, Lady Jean, Anne Hunter, Elizabeth Bell & James Hunter], The journal of Gen. Sir Martin Hunter, G.C.M.G., G.C.H.: and some letters of his wife, Lady Hunter (1894), pp 21-22. St. George himself mentions the foot injury in his letter: "a ball glanced against my ancle & contused it. For some days I was lifted on & off Horseback in Men's arms".Letter from Richard St. George to 'Imperial', 11th September and 2nd October 1777. Wayne Papers, Vol. 4. Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Journal of General Sir Martin Hunter edited by Dickson Hunter, Lady Jean, Anne Hunter, Elizabeth Bell & James Hunter and published by Edinburgh Press, 1894. From the collection of Dan Joyce and photographed at the 'Cost of Revolution: The Life & Death of an Irish Soldier' exhibition at the Museum of the American Revolution.

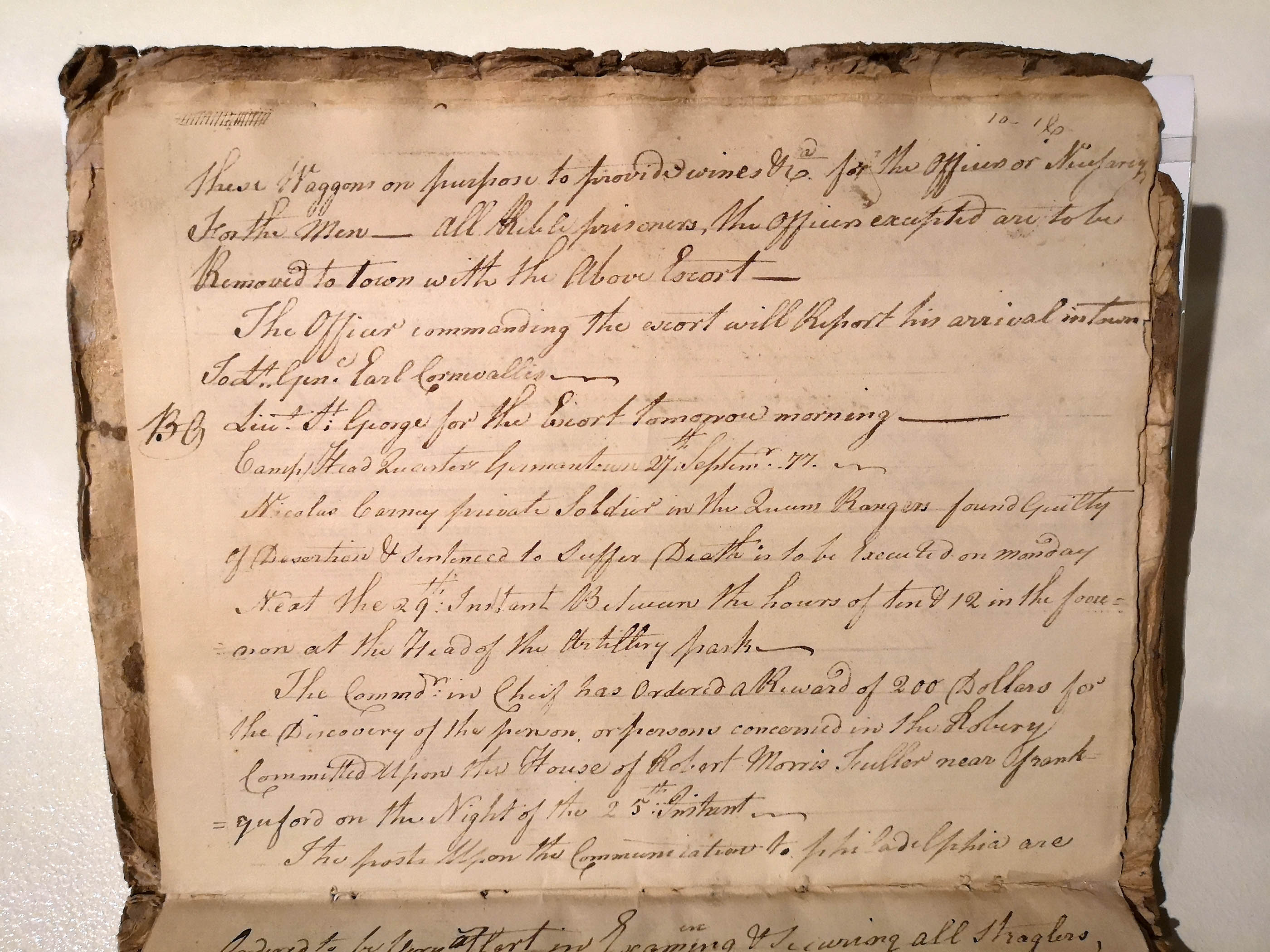

Another interesting detail is that the letter-writer mentioned having seen Philadelphia prior to the Battle of Germantown: "I write from Camp near Beggars TownBeggars Town is now called Mount Airy seven miles distant from Philadelphia [...] I have been there once - Tis a fine [environ]."Letter from Richard St. George to 'Imperial', 11th September and 2nd October 1777. Wayne Papers, Vol. 4. Historical Society of Pennsylvania. It so happens that the orderly book of the British 64th Regiment's Light Infantry, which recorded its daily activities, was also captured by American troops at the Battle of Germantown. It ended up in the possession of General Washington, who used it to gather intelligence about the British, and it is still held in the collection of Washington's papers at the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. The orderly book records the following:

These Waggons on purpose to provide wines &c for the Officers or Necessareys For the Men_

All Rebel prisoners, the Officers excepted are to be Removed to town with the Above Escort_

The Officer commanding the escort will Report his arrival in town To Lt. Gen. Earl Cornwallis_

BOBO = Battalion Orders Lieut. St. George for the Escort tomorrow morning_

Camp Head Quarters Germantown 27th Septemr. 77_Captured British Army Orderly Book, 64th Light Infantry, September 14 - October 3, 1777. Library of Congress, Series 6: Military Papers, 1755-1798, Subseries 6B (B3).

The regiment's orderly book, therefore, clearly names Lieut. St. George as having accompanied an escort to Philadelphia on the morning of 28th September 1777. That was four days before the second part of the letter was written, and six days before it was lost on the battleground at Germantown.

Orderly book of the 64th Regiment's Light Infantry Company (part of the 2nd Battalion of Light Infantry). From the collection of George Washington Papers at the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., and photographed at the 'Cost of Revolution: The Life & Death of an Irish Soldier' exhibition at the Museum of the American Revolution.

Solving the Mystery: For Whom Was The Letter Intended?

Once the author of the letter had been identified as Richard Mansergh St. George, one mystery still remained: for whom was the letter intended? Unusually, St. George does not address the recipient by name, but rather refers to them as "o Imperial".Letter from Richard St. George to 'Imperial', 11th September and 2nd October 1777. Wayne Papers, Vol. 4. Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Again, Sir Martin Hunter provides a clue. He writes: "St George corresponded all the time he was in America with a Mrs --, whom I believe he afterwards married."Hunter, Martin [edited by Dickson Hunter, Lady Jean, Anne Hunter, Elizabeth Bell & James Hunter], The journal of Gen. Sir Martin Hunter, G.C.M.G., G.C.H. : and some letters of his wife, Lady Hunter (1894), pp 21-22. St. George did marry after the war, but not until 1788 when he wed Anne Stepney of Durrow Abbey, Co. Offaly.Burke, Sir Bernard (1912) A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry of Ireland. London: Harrison & Sons, p. 455. See also: Betham, Sir William (1792). Betham Geneaological Abstracts, Series 2, 1595-1799, Vol. 48.

Anne Stepney from 'Mrs. Anne St. George and Child' (1791) by George Romney. From the collection of The Hecksher Museum of Art and photographed at the 'Cost of Revolution: The Life & Death of an Irish Soldier' exhibition at the Museum of the American Revolution.

Anne Stepney from 'Mrs. Anne St. George and Child' (1791) by George Romney. From the collection of The Hecksher Museum of Art and photographed at the 'Cost of Revolution: The Life & Death of an Irish Soldier' exhibition at the Museum of the American Revolution.

Based on Hunter's account, historian Thomas J. McGuire theorised that St. George's fiancée was the intended recipient of the letter.McGuire, Thomas J., The Surprise of Germantown: October 4th 1777 (1994), p. 6. This idea raised even more questions, given that St. George didn't marry Anne Stepney for over a decade after the letter was written. An eleven-year engagament would have been very unusual in the eighteenth century; then again, St. George had been shot in the head at the Battle of Germantown two days after the letter was written and this could very well have necessitated a long engagement. He returned home from the war in 1778 physically and emotionally scarred from combatCost of Revolution: The Life and Death of an Irish Soldier (2019-2020) [Exhibition]. Museum of the American Revolution, 28 September 2019 - 17 March 2020. and spent several years recuperating in ItalyBell, Mrs. G. H. (Ed.), The Hamwood Papers of The Ladies of Llangollen and Caroline Hamilton (1930), p. 74. See also: Letter from Richard Mansergh St. George to Henry Fuseli, reproduced in: Weinglass, David H., The Collected English Letters of Henry Fuseli (1982), p.70. and the south of France.Hunter, Martin [edited by Dickson Hunter, Lady Jean, Anne Hunter, Elizabeth Bell & James Hunter], The journal of Gen. Sir Martin Hunter, G.C.M.G., G.C.H. : and some letters of his wife, Lady Hunter (1894), p. 22. (You can read more about that in the History of Headford Lace.)

St. George always wore a black silk cap after the war to hide the portion of his skull that had been replaced by a silver plate.

Richard Mansergh St George (1791) by Hugh Douglas Hamilton. From a private collection, photographed at the 'Cost of Revolution: The Life & Death of an Irish Soldier' exhibition at the Museum of the American Revolution.

I was intrigued by Hunter's comment and the theories surrounding it ... Who was this married woman with whom St. George puportedly corresponded? Why did Sir Martin Hunter not name her? Was she still married at the time of writing, or was she perhaps a widow? Did St. George really marry her afterwards? If so, was Anne Stepney the lady to whom Hunter referred? Had they really been engaged for eleven years? Or had St. George been married to someone else before her?

Further research eventually led me to a document that explained this conundrum: in 1788, The Gentleman's and London Magazine published the following:

MARRIAGES for Jan. and Feb. 1788. [...] In London, Mansergh St. George, Esq. to Mrs Doyne, relict of the late Benjamin Burton Doyne, of the county of Carlow, Esq No author, 'Marriages for Jan. and Feb. 1788' in 'The Gentleman's and London Magazine: Or, Monthly Chronologer' (1788) Dublin: John Exshaw, p. 111.

This document shows that Anne Stepney, whom St. George married in early 1788, was the widow of Benjamin Burton Doyne Esq. of Co. Carlow. When St. George had been writing to her in 1777, she would have been known as Mrs. Burton Doyne,Brewer, James Norris, The Beauties of Ireland: Being Original Delineations, Topographical, Historical, and Biographical, of Each County, Vol. I (1825), pp 391-392. making Hunter's account entirely accurate. I afterwards found a manuscript in the National Library of Ireland, which corroborates that the wife of Richard Mansergh of Headford, Co. Galway, was the daughter of a man named Stepney and widow of a man named Doyne. Registered Pedigrees Vol.16; ca.1816-1817. National Library of Ireland: GO MS 170, p. 119.

The combined findings of American researchers in recent decades have led to new channels of investigation for research here in Ireland, which led me to this discovery of a previously unknown aspect of St. George's relationship with his wife. This discovery now also gives greater context to the 1777 letter for those studying the American Revolution, as well as confirming the veracity of Hunter's account of St. George. I am very grateful to the Museum of the American Revolution and Matthew Skic for facilitating my attendance at the 2019 International Conference on the American Revolution, which has fostered this cross-pollination of ideas across the Atlantic Ocean.

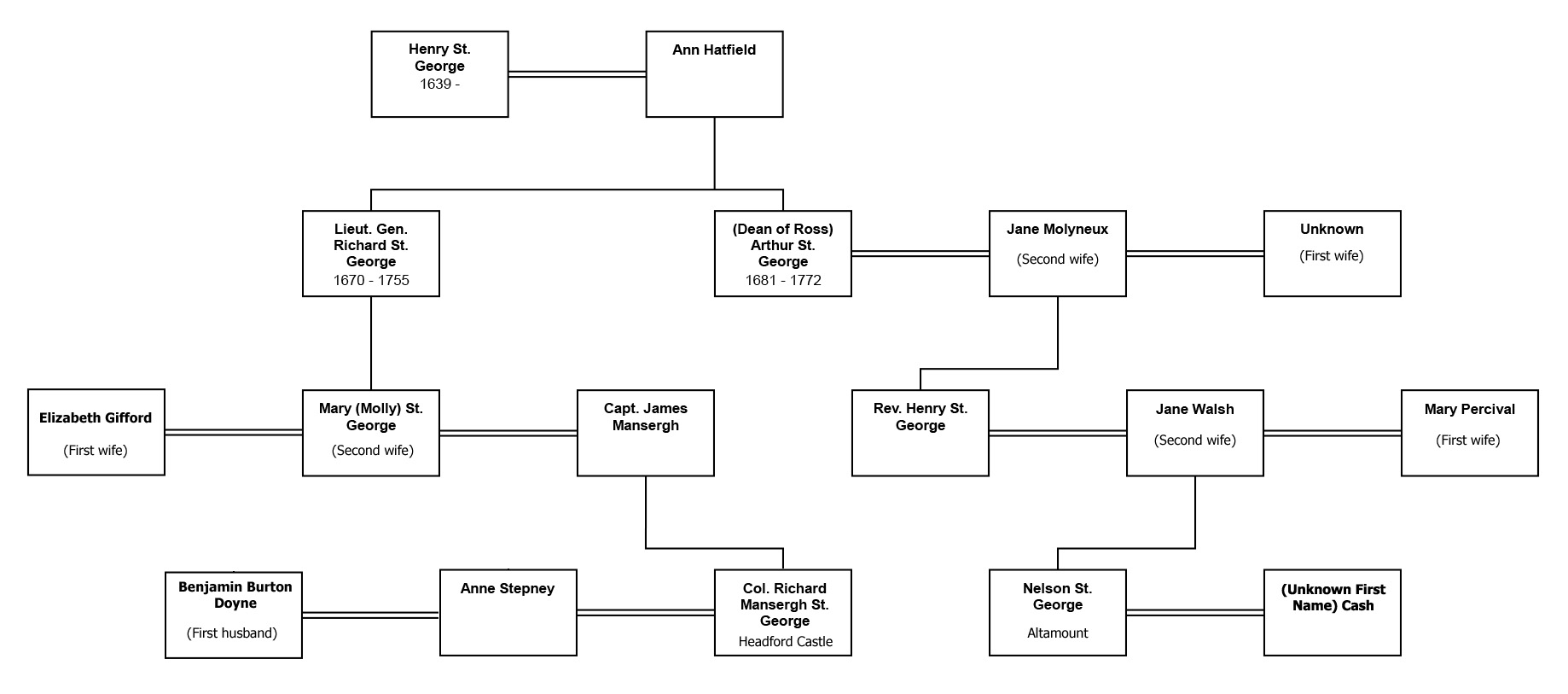

Anne Stepney & Benjamin Burton Doyne

Stepney and Doyne had been married on 23 February 1768.Burke, Bernard, A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry of Ireland (1912), p.193. They lived at Altamount House in Co. CarlowIbid. - which had actually been lived in and remodelled during the 1740sBrennan, Michael (2001) 'Altamount House, Tullow, Carlow' at Carlow County - Ireland Genealogical Projects. by Nelson St. George,Lewis, Samuel, 'Ballon' in A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland Comprising the Several Counties, Cities, Boroughs, Corporate, Market, and Post Towns, Parishes and Villages with Historical and Statistical Descriptions, Vol. I (1840), p. 121.who was a second cousin of Richard Mansergh St. George.Burke, John & Burke, John Bernard, A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain & Ireland, Vol. II - M-Z (1846), p. 1176. Indeed, it may have been through this Nelson St. George that Anne Stepney and Richard Mansergh St. George came to know one another.

Altamount House was bequeated to the Irish State in 1999 and has been managed by the Office of Public Works ever since.Irish Times, 28 Dec. 2007. See also: O'Byrne, Robert. 'Developments Awaited', 16 July 2018. The house is currently undergoing restoration, but the 19th-century gardens are open to the public.

Altamount House, Co. Carlow.

Altamount House, Co. Carlow.

Anne Stepney was considered "one of the most admired beauties of her day".Brewer, James Norris, The Beauties of Ireland: Being Original Delineations, Topographical, Historical, and Biographical, of Each County, Vol. I (1825), pp. 391-392. George Ogle of Belleview, Ballyhogue (who would later become M.P. for Wexford) wrote a song called 'Shepherds I Have Lost My Love' that was inspired by "Miss Stepney, of Durrow-house, Queen's county,Queen's County is an old British colonical name for County Offaly afterwards Mrs. Burton Doyne, of Wells".Brewer, James Norris, The Beauties of Ireland: Being Original Delineations, Topographical, Historical, and Biographical, of Each County, Vol. I (1825), pp. 391-392. The lyrics say:

Shepherds I have lost my love,

Have you seen my Anna?

She's the Pride of ev'ry Grove

Upon the banks of Banna.The Banna is a stream near Gorey, Co. Wexford.

I for her my home forsook,

Near you misty Mountain,

Left my Flock, my Pipe, my Crook,

My Green-wood Shade and Fountain.

Never shall I see them more,

Untill her returning,

All the joys of Love are o'er,

From gladness chang'd to Mourning;

Whither is my Charmer flown,

Shepherds tell me whither,

Ah! woe is me perhaps She's gone

Forever and forever.Ogle, George; Tenducci, Giusto Fernando; Rauzzini Venanzio (c.1782). 'Shepherds I have lost my love'. London: Rauzzini, Longman & Broderip.

George Ogle (c.1777) by an unknown artist. Image in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The circumstances in which Richard Mansergh St. George and Mrs. Burton Doyne met are not known, and we can only speculate as to the nature of their long relationship. However, in 1786, Benjamin Burton Doyne wrote a will which he declared made "void all other Wills by me heretofore made".Part of this sum was assigned by Benjamin Burton Doyne to George Bunbury Esq. See: Will and administration of Benjamin Burton Doyne (Altamount, Carlow) 12 December 1786. National Library of Ireland: Ms 29,770/37 - Doyne Family and Estate Papers, c. 1660-1939. In it, he mentions "the sum of Two thousand pounds ster[ling,] My Wife's Portion and all Interest due thereon which I am now sueing for in the Court of Chancery".Part of this sum of £200, for which Doyne was suing his wife, was assigned by him to George Bunbury Esq. See: Will and administration of Benjamin Burton Doyne (Altamount, Carlow) 12 December 1786. National Library of Ireland: Ms 29,770/37 - Doyne Family and Estate Papers, c. 1660-1939. The marriage portion is similar to a dowry, and it is very unusual that a husband would sue his wife for this money at the Court of Chancery. It suggests that their marital relationship was strained. Furthermore, Doyne makes no provision for his wife in the will, and instead leaves everything to his brother, Robert Doyne - save for "the sum of Two hundred pounds which I Bequeath to my Natural Daughter Deborah Doyne".Will and administration of Benjamin Burton Doyne (Altamount, Carlow) 12 December 1786. National Library of Ireland: Ms 29,770/37 - Doyne Family and Estate Papers, c. 1660-1939. At the time of writing, it is unknown whether his daughter was born before or after Doyne's marriage. Doyne and Stepney would have no children together.

The will is dated 12th December 1786, and Doyne may have been unwell at the time of writing as he died just a couple of months later. Benjamin Burton Doyne was buried at Rathvilly, near Tullow, Co. Carlow, on 12 February 1787.Church of Ireland (1787) 'A Register for the Parishes of Tullophelim, Ravilley &c' (1696-1825).

Anne Stepney & Richard Mansergh St. George

As was noted above, Anne Burton Doyne née Stepney married Richard Mansergh St. George in early 1788 (January-February). They would have two children together, both sons: Richard James (born 16 October 1789) and Stepney (born 17 March 1791).Bernard Burke, A genealogical and heraldic history of the landed gentry of Great Britain & Ireland (7th ed., London, 1886), p. 1604.

A few months after their marriage, on Wednesday, 23rd July 1788, Lady Eleanor Butler of the so-called 'Ladies of Llangollen' writes in her diary: "Col. and Mrs. St. George and Miss Stepney purpose settling in the neighbourhood of Llangollen if they can get a House."Bell, Mrs. G. H. (John Travers), Ed., The Hamwood Papers of The Ladies of Llangollen and Caroline Hamilton (1930), p. 115. It seems that the St. Georges were successful in settling in Wales, as just five days later, on 28th July, Lady Butler referred to Anne and her sister as "our neighbours Mrs. St. George and Miss Stepney".Bell, Mrs. G. H. (John Travers), Ed. (1930) The Hamwood Papers of The Ladies of Llangollen and Caroline Hamilton. London: Macmillan and Co., p. 118. We know that the couple also spent some time at their property at Clifton, near Bristol in England (where, in 1783, St. George had hosted a medieval pageant for his friends, artist Henri Fuseli, poet Anna Seward, and Sir Brooke Boothby.Myrone, Martin, 'Gothic Romance and the Quixotic Hero: A Pageant for Henry Fuseli in 1783', in Tate Papers, No.1, Spring 2004. ) In Ireland, St. George had two estates: Macroney Castle, near Fermoy in Co. Cork, which he inherited from his father, Capt. James Mansergh; and Headford Castle in Co. Galway, which he inherited from his mother, Mary St. George. Assessing his estate at Heaford in 1790, St. George wrote the first contemporary reference to Headford Lace with the words: "The women at Headford make lace".St George, Richard St. George Mansergh (1790) 'An account of Galway by Richard St. George Mansergh St. George'. IE TCD MS 1749/2, Trinity College Dublin.

Three short years into their marriage, in the summer of 1791, Anne was diagnosed with a fatal illness. St. George wrote that it was then that "the physicians informed me of the fatal symptoms"Letter from Richard Mansergh St. George to artist Henry Fuseli, reproduced in: Weinglass, David H.,The Collected English Letters of Henry Fuseli (1982), p.71. On hearing the news, St. George commissioned George Romney to paint her portrait (pictured below), for which he paid two hundred guineas in advance.Ward, Humphry & Roberts, W. (1904) Romney: A Biographical and Critical Essay with a Catalogue Raisonné of his Works, Vol. II. London, Manchester & Liverpool: Thos. Agnew & Sons, p. 138. Mrs. St. George, dressed in peasant style,Kidson, Alex, George Romney: A Complete Catalogue of his Paintings, Vol. II (2015), pp 515-516 is depicted "sitting, in white dress, grey shawl, head draped with white".Ward, Humphry & Roberts, W. (1904) Romney: A Biographical and Critical Essay with a Catalogue Raisonné of his Works, Vol. II. London, Manchester & Liverpool: Thos. Agnew & Sons, p. 138. She sat for the artist three times between July and August 1791, while her eldest son, Richard, who appears in the portrait with her, posed ten times. Romney was also invited to dine with the family one Saturday afternoonWard, Humphry & Roberts, W., Romney: A Biographical and Critical Essay with a Catalogue Raisonné of his Works, Vol. II (1904), p. 138. - possibly as a way for the artist to become acquainted with her character, which some people believed to be "as great an advantage as a sitting".Mr. Edward Tighe in: Herbert, J.D., Irish Varieties for the Last Fifty Years: Written from Recollections (1836), p. 29.

'Mrs. Anne St. George and Child' (1791) by George Romney. From the collection of The Hecksher Museum of Art and photographed at the 'Cost of Revolution: The Life & Death of an Irish Soldier' exhibition at the Museum of the American Revolution.

'Mrs. Anne St. George and Child' (1791) by George Romney. From the collection of The Hecksher Museum of Art and photographed at the 'Cost of Revolution: The Life & Death of an Irish Soldier' exhibition at the Museum of the American Revolution.

Anne passed away at Clifton (near Bristol) a year later, in August 1792.Bury and Norwich Post, 22 Aug. 1792; Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 23 Aug. 1792; Norfolk Chronicle, 25 Aug. 1792. The cause was apparently "The Lungs destroyed".Letter from Richard Mansergh St. George to artist Henry Fuseli, reproduced in: Weinglass, David H., The Collected English Letters of Henry Fuseli (1982), p.69. St. George brought the remains of his wife home to Ireland for burial, arriving into Dublin from Bristol aboard the 'Flora' on 28 October.Dublin Evening Post, 30 Oct. 1792; Dublin Evening Post, 03 Nov. 1792. She was buried with the St. George family at St. Mary's Church of Ireland in Athlone on 3rd November.Church of Ireland Register of Births, Marriages, and Deaths for the Parish of St. Mary Athlone, Diocese of Meath, 1746-1797. 'Burials', p.52. RCB Library, Dublin.

Grief-stricken after his wife's death, St George wrote to his friend, the artist Henry Fuseli, saying: "I have lost lost all - the balm of Life"Letter from Richard Mansergh St. George to artist Henry Fuseli, reproduced in: Weinglass, David H. (1982) The Collected English Letters of Henry Fuseli. New York & London: Kraus International Publications, p.67. His grief compounded the melancholy he often suffered following the brain injury he sustained in the war, and he was frequently characterised as depressed,Trench, Richard Chenevix (Ed.), The Remains of Mrs. Richard Trench, being Selections from her Journals, Letters, & Other Papers, Edited by Her Son, The Dean of Westminster (1862), p. 247. or "gloomy"; even "under a fit of insanity"Herbert, J.D., Irish Varieties for the Last Fifty Years: Written from Recollections (1836), p. 44.

Following his wife's death, St. George became increasingly obsessed with his own mortality. This sprang not only from his mental state, but also out of a practical concern for his children, coupled with an acute awareness of his own "very delicate state of health".Freeman's Journal, 15 Feb. 1798. He writes to Fuseli that his boys' "future happiness [and] Education employd my Thoughts in moments I wish to God I coud forget and produced volumes of Instructions to Their Guardians in the Intervals of Convulsive fits, in Intervals more terrible and painful to Me -"Letter from Richard Mansergh St. George to artist Henry Fuseli, reproduced in: Weinglass, David H., The Collected English Letters of Henry Fuseli (1982), p.67.

St. George was preoccupied not just with providing for the material needs of his children, but also with ensuring their sense of connection with their parents should they become orphaned. He devised an elaborate plan whereby the portrait of their mother and a new one he would commission of himself would be locked in a secret room, the key to be given to his boys when they would reach maturity so that "The Images of their Father and Mother may appear to Them". Letter from Richard Mansergh St. George to artist Henry Fuseli, reproduced in: Weinglass, David H., The Collected English Letters of Henry Fuseli (1982), p.67. St. George did eventually appoint Hugh Douglas Hamilton to paint a mourning portrait, in which he is depicted with an anguished expression and leaning against an idealised version of his wife's tomb, which is incribed with the words Non Immemor (Never Forget). The jabot worn at his neck is trimmed with Headford Lace (read more about that here).

'Lieutenant Richard Mansergh St. George' (c.1796) by Hugh Douglas Hamilton. From the collection of the National Gallery of Ireland and photographed at the 'Cost of Revolution: The Life & Death of an Irish Soldier' exhibition at the Museum of the American Revolution.

It appears that St. George did not, however, follow through with his plan for the paintings, as the portrait of Mrs. St. George remained in the artist's studio until 1802.Kidson, Alex, George Romney: A Complete Catalogue of his Paintings, Vol. II (2015), p. 516. It was eventually sent over to the family seat at Headford Castle, where it hung until about 1888, at which time it came into the possession of her granddaughter in London, Mrs. E. Winn.Ward, Humphry & Roberts, W., Romney: A Biographical and Critical Essay with a Catalogue Raisonné of his Works, Vol. II (1904), p. 138; Kidson, Alex, George Romney: A Complete Catalogue of his Paintings, Vol. II (2015), p. 515. Headford Castle was sold in 1892Tuam Herald, 18 Jun. 1892. and was no longer in the St. George family after that. The castle was destroyed in an accidental fire in 1906.Tuam Herald, 30 Jun. 1906; Western People, 30 Jun. 1906.

When St. George's mourning portrait was exhibited at the Dublin exhibitions in 1801, one visitor declared that it described "a man versed in misfortune, whose accounts with this world are closed and who cares not how soon he should be removed to another."Cullen, Fintan, Sources in Irish Art: A Reader (2000), p. 240. Indeed, during the 1798 Rebellion just six years after his wife's passing, St. George met his own end. He was killed on the night of 9th February by rebels on his Co. Cork estate . He had been staying at the house of his land agent, Jasper Uniacke, at the time. Uniacke also lost his life that night, and Uniacke's wife sustained injuries in the attack. Three men - John Hickey, John Hoy, and Patrick Hynes - were identified by Mrs. Uniacke'Interesting Intelligence from Ireland.- Important Trials. [...] Cork, April 14' in The Gentleman's Magazine, April 1798, pp.346-347. and subsequently tried and hanged for the murders.'Comóradh 1798 - Bicentenary of 1798' (1998) 'At Carey's Lodge, Araglin on 9th February, 1798 Col. Richard Mansergh St. George, landlord, magistrate and vigorous opponent of the United Irishmen[,] and his host Jasper Uniacke were killed by a band of United Irishmen[.] Having been convicted for these killings[,] John Hickey and John Hoy were hanged here on 16th April, 1798[,] and Patrick Hynes was hanged at the Gallows Green in cork on 18th April, 1798. Ar dheis Dé go raibh a h-anamnacha'. Monument at Araglin, Co. Cork. (Viewed: 14 October 2019).

Memorial at the site where St. George and Uniacke were killed in 1798, and where those convicted of their murder were subsequently hung.

Memorial at the site where St. George and Uniacke were killed in 1798, and where those convicted of their murder were subsequently hung.

On Monday 12th February, "at ten at night, the remains of the late Mansergh St. George, Esq. were carried in great funeral pomp for internment. The military and yeomanry attended this mournful procession [and] a discourse suited to the melancholy occasion was pronounced by the Rev. Mr. Sterling.'Finn's Leinster Journal, 28 Mar. 1798. Richard Mansergh St. George was "intered [sic] in the Family Vault" at St. Mary's Church of Ireland in Athlone, Co. Westmeath on 22nd February 1798.Church of Ireland Register of Births, Marriages, and Deaths for the Parish of St. Mary Athlone, Diocese of Meath, 1797-1824. 'Burials', p.2.RCB Library, Dublin.

The St. George Family & Headford Lace

Richard Mansergh St. George had been a great patron of Headford Lace throughout his life: he himself wore Headford Lace, he encouraged the industry and markets, and he built the cottages in New Street c.1790 to house lacemakers and other craft workers. No history of Headford Lace is complete without reference to this man, and understanding his life helps us to better appreciate the social context for the lace industry in the early decades after its foundation.

Transcription of the 1777 Letter

From the Camp on the Field of Battle near Dilworth, on the heights of Brandy Wine, September 11th at night.

I shou'd have written to Thee o Imperial - consider the pain of the contusion! What excessive fatigue - a rapid march from 4 o'clock in the morning till four in the eve, when we engaged - till Dark we fought. Describe the Battle - 'Twas not like those of Covent Garden or Drury Lane. Thou has seen Le Bruns paintings and the Tapestry perhaps at Blenheim - are these natural resemblances? pshaw - quoth 'The Captain' in un mot. There was a most infernal Fire of cannon & [musketry] - most incessant shouting - incline to the right! incline to the left! halt! charge &c. The balls ploughing up the ground. The Trees cracking over ones head. The branches riven by the artillery - The leaves falling as in autumn by the grapeshot. The affair was general. The Misters on both sides shew'd conduct. The action was brilliant. Mr. Washington retreated (i.e. run away) and Mr. Howe remained Master of the Field. We took ten pieces of cannon & a Howitzer - 8 were brass - the other two iron of a new construction. I took a high cap lined with fur which I find very comfortable in the now "not Summer evenings in my Tent." a ball glanced against my ancle & contused it. For some days I was lifted on & off Horseback in Men's arms - understand - I do not write from the Camp on the Field of Battle &c. &c., neither do I write in the month of September. Since the above Date I have been in a more bloody affair.

At midnight on the 22nd of Septm:er the Batt when I serve in (the 2d of Light Infantry) supported by Three Regiments & some Dragoons, surprised a Camp of the Rebels consisting of 1500 men & bayoneted (we hear) from 4 to 500. The affair was [admirably] conceived and executed. I will (as it is remarkable) particularize - I was relieved from picquet at Sunset (the preceeding sunset I mounted) and was waked at nine at night to go on the bloody business. The men were ordered to unload - on no account to fire. We took a circuit in Dead silence. About one in the morning fell in with a rebel vadet (a vadet is a Horse Centenel) who challenged three times and fired. He was pursued but escaped. Soon after Two foot Centrys challenged and fired - who escaped also. We then marched on briskly still silent - our Company was advanced immediately preceeding a Company of Rifleman who always are in front - a picquet fired upon us at the distance of fifteen yeards miraculously without effect. This unfortunate Guard was instantly dispatched by the Riflemen's swords. We rushed on thro a thick wood and received a smart fire from another unfortunate Picquet, as the first instantly massacred. We then saw their wigwams or Huts partly by almost extinguished light of their fires & partly by the [light] of a few stars & the frightened wretches endeavouring to form - we then charged - For two miles we drove them now and then [firing] scatteringly from behind fences Trees &c. The flashes of the pieces had a fine effect in the night - then followed a dreadful scene of Havock. The Light Dragoons came on Sword in Hand - the Shrieks, Groans, Shouting, imprecations, deprecations, The Clashing of swords & bayonets &c. &c. &c. (no firing from us & little from them except now & then a few as I said before scattering shots) was more expressive of Horror than all the Thunder of the artillery &c on the Day of action. They threaten retaliation, vow that they will give no quarter to any of our Battalions - We are always on the advanced Post of the army - our Present one is unpleasant - our left too open & unguarded. We expect reinforcements.

There has been firing this night all round the Centrys - which seems as if they endeavour to feel our situation. I am fatigued & must sleep. Coud'st THOU sleep? - thus - No more than I cou'd act Sr Wildair in a ship on fire - nor I at first - (entre nous) - but Tyrant Custom &c., yet my rest [is] interrupted - I wake once or twice [eer morning] my Ear is susceptible of the least noise.

Mr. Washington by the account of some come in to day is eighteen miles distant with his main Body - they also say He intends to move nearer us resolved to [try] the event of another Battle. He has been reinforced. Before the action of the 11th. of Septemb & the nocturnal bloody scene our Battalion had a skirmish with Genll Maxwells light Troops whom we drove from a very strong pass on the Iron Hills.

N.B. I write from Camp near Beggars Town seven miles distant from Philadelphia, which is garrisoned at present by the British & Hessian Grenediers under Lord Cornwallis - I have been there once - Tis a fine [environ.]

Octobr 2, 12 midnight in my Tent.